Dear friends,

My seven-year-old daughter is learning about the space race at school. She’s also learning cheesy Christmas songs and has become an ardent fan of Mariah Carey.

This has led to some bizarre cross-pollination.

Yesterday she was dancing around the kitchen singing:

‘All I want for Christmaaas is Yooo-ri Gagarin!

All I want for Christmaaas is President Nixon!’

Meanwhile my four-year-old son has been given the role of one of the three kings in his class nativity.

It’s a solid part, by any standards, but he’s not happy. He wanted to be a donkey. ‘I want to be an animal!’ he shouted in the car. ‘I don’t want to be a human!’

This has been a theme of recent months. A while ago he told me that he doesn’t ‘want to be an adult never – because I don’t like being human!’

He has quite a fluid relationship with other species. He often pretends to be different animals and it’s clear, watching him prowl or creep or bounce, that he believes, in that moment, that he is that animal.

He passes this fluidity onto our toys. He recently took the head off a doll and fitted it over the head of a plastic walrus. ‘Now it’s part-walrus, part-baby’, he said. He made the walrus-baby play with the headless doll. ‘His friend is his own body,’ he said. ‘His own friend is his own body.’

My son is even open to the animality of plants. ‘What do the bones of flowers look like?’ he asked me.

As well as being deeply interested in animals, my son has a very casual relationship with fact. He likes to offer spurious information, backed up by authoritative sources. ‘Giraffes don’t have hearts,’ he told me a couple of weeks ago. ‘I’ve learned that at school’.

At school he also learned that ‘baby dragons are the size of cats’.

All of this is to say that my son keeps animals and animality on the agenda in our house. They are a constant theme of conversation.

We have a couple of pet fish in our kitchen, but my son and daughter would love us to have a big, proper pet. Preferably a sausage dog. Or – ideally – several sausage dogs.

But we’re a Diplomatic family. We lived in Argentina for four and a half years. We’re in Cyprus now. We know a lot of Diplomatic families who have adopted stray animals on a posting and then spent thousands of pounds getting them passports and shipping them around the globe.

We are determined not to become one of those families.

Last Thursday morning I was working in my office, focusing hard, trying to meet multiple deadlines. A couple of hours into my day I went to stand on the balcony in the sunshine, stretching my legs and looking at the mountains beyond our village. I was about to return to my laptop when I saw a rock in the road outside.

Except that, even without looking closely, I knew it wasn’t a rock. It was the grey-brown shell of a tortoise and it was sheltering below the wheel of a parked car, waiting to be crushed.

I ran outside, crossed the road and picked it up. Its legs twitched and it tucked its head more firmly inside its shell. I looked around. Where had it come from? I wandered along the road for a minute, glancing about for potential tortoise owners.

I could hear a voice in the garden nearest the car where I’d found the tortoise. Peering over the gate I saw a forty-something man at an outside table on a Zoom call. I waved at him. He glanced at me, then stared back at the screen and continued talking. It was not a good time. Nevertheless, I waved again, wielding the tortoise at him over the gate. He looked at the tortoise in disbelief, excused himself from the call and walked over.

‘Is this your tortoise?’ I asked. ‘I just found it in the road.’

He stared at the tortoise, trying to square this sudden encounter with a reptile with the Zoom call he’d just been immersed in.

‘No’, he said, ‘its not ours’ and rushed back to his computer.

There was nothing to do but take the tortoise home – back to the house where my laptop and deadlines were waiting.

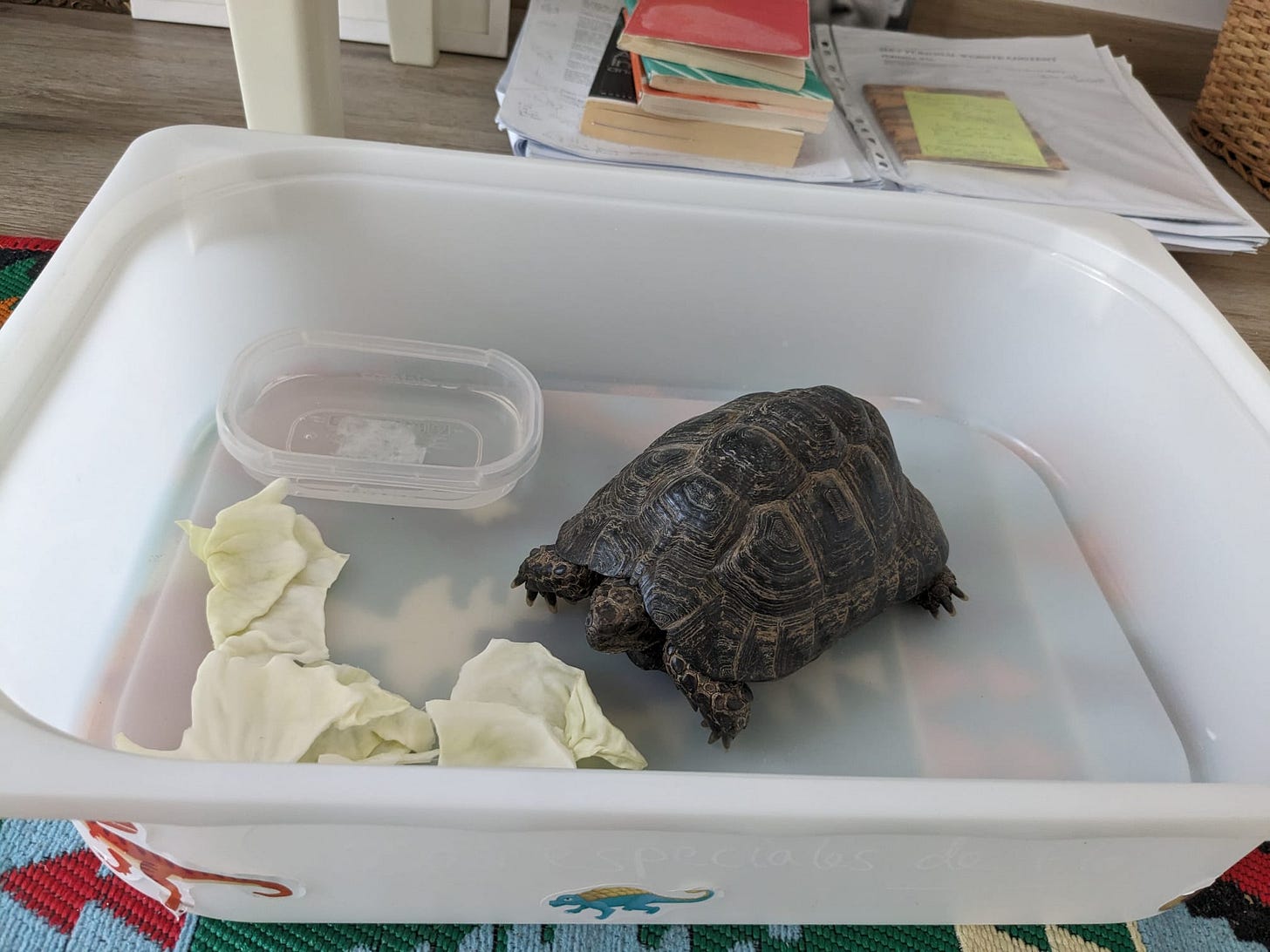

In the house I put the tortoise into a plastic tray with some cabbage and water.

I then realised that the tray was preposterously small and moved the tortoise to the bath. There too it pawed at the corners, desperate to climb out.

So I picked up the tortoise and moved it to the balcony. Further down the street I could see an older man crossing the road. He looked, to me, like he might be searching for a tortoise.

‘HAVE YOU LOST A TORTOISE?’ I shouted. He stared at me, bewildered. The tortoise folded its legs and head into its shell and I left it in peace.

What do you do with a tortoise?

I was glad I had rescued it from near-certain death, but now I was the custodian of a creature I had no idea how to care for.

I sent some messages. The advice flowed in.

Tortoises can’t eat spinach.They can eat fruit but not too much.They can eat lettuce but not iceberg.They need cuttlebone, or calcium sprinkle, for their shell.Don’t pick up them by the sides; put your hand underneath.Wash your hands – they may be carrying salmonella.Tortoises are surprisingly interactive.They are supremely fascinating and soothing.I looked away from my phone. I tried to forget the tortoise for a while and do some work.

I strongly suspected the tortoise was someone’s pet. My googling indicated that they are not indigenous – but it also made clear that Cyprus is now host to generations of stray tortoises, descended from lost pets. Which one was this?

Our village is full of loose and stray animals. Dogs amble past. Stray cats lounge in the heat and congregate at sunset on a ledge above the valley, where an older man comes, without fail, to feed them. Perhaps this tortoise had spent its life pottering around our village and I, in a fit of misplaced concern, had abducted it.

I just didn’t know.

My wife and I decided that we’d ask our daughter to make a HAVE YOU LOST THIS TORTOISE poster and we’d put a message on the village Facebook group.

There were lots of enthusiastic potential tortoise-adopters, but nobody seemed to have lost one. My wife and I talked about it later. Maybe, if no one claimed the tortoise, we should keep it? The kids would love it.

I went out for the evening.

When I got back I found my wife staring at her laptop. ‘I’ve been looking at visas for tortoises,’ she said.

The next day a woman from a hundred metres down the road posted on Facebook that she had recently lost a tortoise and would love to come round.

How many lost tortoises can there be within a one hundred metre radius? She had lost a tortoise. We had found a tortoise. Bingo.

I felt strange about it though. I’d been starting to feel like perhaps it was fate that I’d found the tortoise in the road. I work alone a lot; out of nowhere, a companion had appeared. Perhaps it was going to become part of our family. My son had decided it was a boy and named it Bobby.

But we were glad we’d found the owner and we braced ourselves for Bobby’s departure.

In the build up to our neighbour’s visit I became convinced that she was a scammer, pretending she’d lost a tortoise in order to make off with Bobby. I insisted to my wife that we needed to see photographic proof of ownership.

When the woman came around, she was a delightful, knowledgeable tortoise enthusiast. She had two of them at her house and one had recently orchestrated a great escape from her garden, climbing a tree and making a bid for freedom. He was a teenager, she said, and liked to headbutt people’s legs.

Bobby had not tried to headbutt our legs.

When the woman stepped onto the balcony she declared immediately that Bobby was far too small and definitely not her tortoise.

She went away and, suddenly, there we were again, caring for Bobby, confronted with the improbable reality that there were multiple lost tortoises wandering the streets of the village.

Did you know that tortoises drink water through their tails?

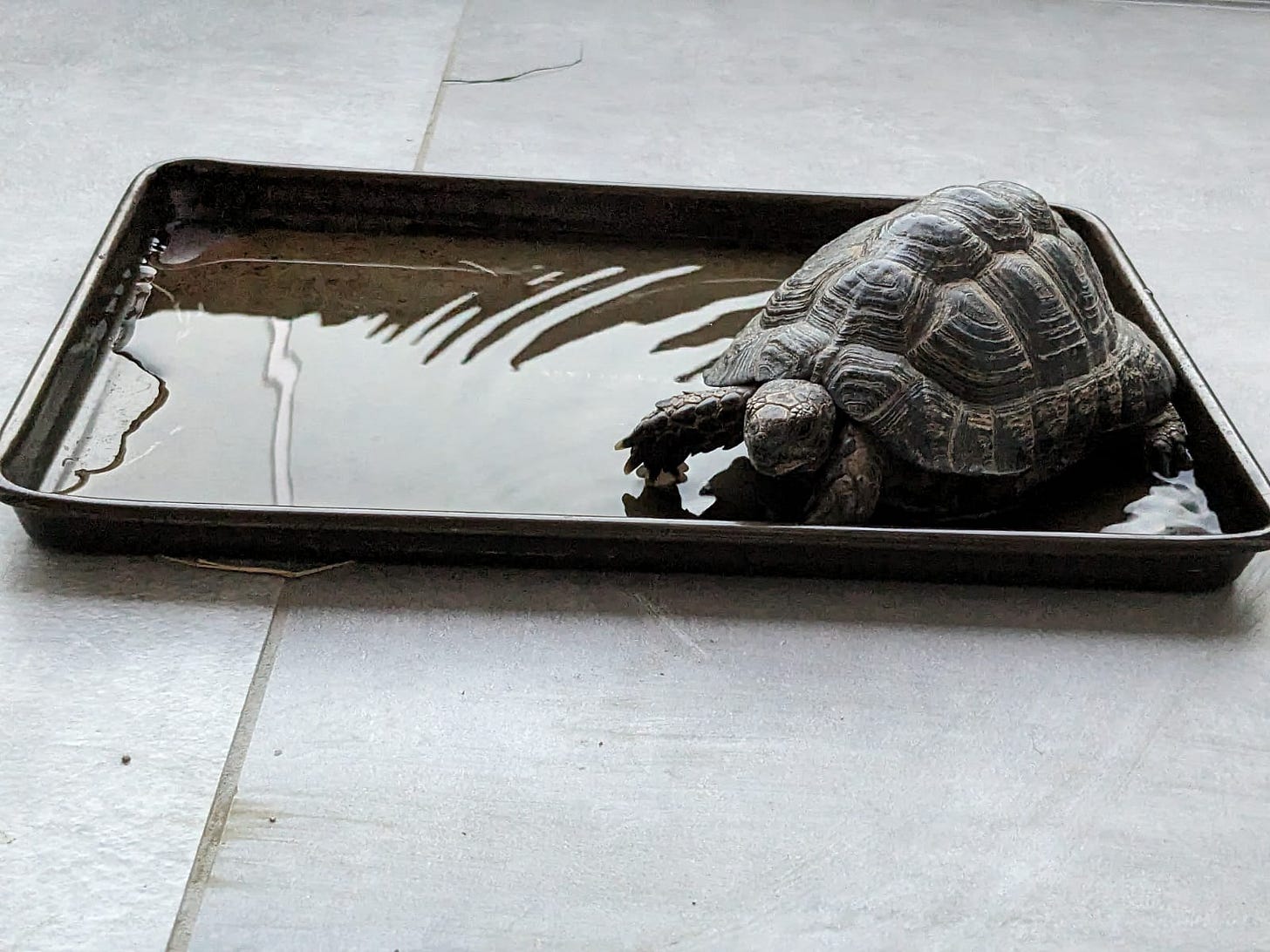

This was one of the gobbets of information that reached us in our pursuit of tortoise care guidance. We would need to bathe Bobby for at least ten minutes a day, so that he could refresh and hydrate.

We gave Bobby his first bath and built him a bed from a foam pad and a cereal box, to insulate him from the cold, hard balcony.

Days passed and Bobby and I settled into a routine. The kids went to school, my wife went to work, and Bobby and I got on with our business at home.

I was glad of his company, but I had mixed feelings. Every time I popped out to see Bobby, he hid inside his shell. Although our tortoise-loving neighbour insisted that tortoises like having their shell scratched, Bobby was unresponsive to my attempts at tortoise massage. I felt that we were struggling to connect.

Bobby did laps of the balcony, stopping occasionally to eat a leaf or a piece of cherry tomato.

It didn’t look like much of a life, pacing a couple of metres of cold stone. From feeling like Bobby’s rescuer, I began to feel like his jailer.

When I mentioned Bobby to friends, they were charmed but also stressed the responsibility of owning a tortoise. ‘You’ll need to put it in your will’, one person said, ‘because it’ll probably outlive you.’

One minute I’d found Bobby in the street. Now I was considering arrangements for his care after my demise.

‘A friend of mine wants a tortoise for her fortieth birthday,’ another friend said, ‘so that she’ll have a pet that’s with her to the end.’

I looked at Bobby, pootling around the balcony. Were we ready for this?

My wife and I had a sit-down chat about Bobby. If no owner emerged, would we keep him?

Our doubts about our suitability were compounded by the lukewarm reaction from our children. They liked Bobby, but less than we had imagined. My son was more excited about pretending to be a tortoise, than watching one plod round the balcony.

We got back in touch with our tortoise-loving neighbour. Bobby would have a better life with her. She let her tortoises roam free around the house. She gave them soothing shell rubs. Bobby could shack up with her remaining tortoise Michelangelo.

We sent her a message and asked if she wanted to adopt Bobby.

On my last day with Bobby, I reflected on how we had been thrown together.

He had appeared so close to our house it was impossible to ignore him, impossible not to feel like he was our responsibility.

What if Bobby had been twenty metres further down the road? Would I have taken him in then?

At what point does something undeniably become our business? When do we unavoidably intervene?

The neighbour wrote back to say that she would love to adopt Bobby. Soon it would be time to hibernate and Bobby could dig a hole in her garden and nestle in for the winter.

Bobby left a week after we found him, moving to live with a family with genuine tortoise know-how and with his new friend Michelangelo. Still, it felt strange saying goodbye after a week of co-living and co-working. As the family drove away, I walked back to my desk and my deadlines, eyeing the balcony, littered with scraps of veg.

I’m glad we found Bobby. I’m glad he came to stay. Now when I leave the house, I can’t help scanning the curbs and corners for the other lost tortoise, wondering if this whole strange experience will repeat itself.

Warm wishes,

Matt

Matt, this is so brilliantly described. I love it. I've got to say though, your son is giving some very sound advice re: being your own friend to your own body! He should be a philosopher. Or a life coach. xx