#4 Watching Zorro with Patrick

A community imagining the world differently

Dear friends,

The drive to my children’s school is along a winding clifftop road. Through one window we can see the Mediterranean, through the other miles of thorny scrub, dotted with radio masts and the ruins of an ancient city state.

As I was driving my children home at the end of last week, I noticed a cloud of yellow smoke ahead. We rounded a bend and found ourselves next to a small wildfire. Its flames were devouring the dried-out bushes at the roadside, licking at the juniper and carob trees, while a group of firefighters and locals battled to put it out.

I slowed the car down. This summer we’ve seen smoke above the mountainsides, helicopters passing overhead with giant buckets slung beneath them. We’ve seen the grey smear across the horizon after wildfires in Turkey and Greece. But we’ve never seen one up close. The late afternoon sun backlit the scene and, for an instant, looking through the low sun, the fumes, the flames, the whole landscape blazed. I crept past, reassured that the firefighters seemed to have the upper hand, then sped away.

In the back of the car, my children were discussing the concept of fairness, concluding that they like it when things are ‘fair for them’ and not when things are ‘fair for other people’. ‘They’re doing a good job putting out that fire,’ I said. ‘What fire?’ they replied.

It’s been a scorching summer in Cyprus. There is a sense here, like everywhere, that the seasons are coming loose from our beliefs about them. We reach for the word ‘unseasonable’ with alarming frequency.

Yet somehow, amid the dust and heat, figs are ripening on the trees. I don’t understand it – the way they alchemise soft fruit from dry ground.

There is a fig tree in our valley I’ve had my eye on for months, a huge sprawling thing the height of a house. Jogging past it, the smell of the fruit is overwhelming. Yet whenever I stop to pick ripe figs, I can’t find any. Someone else must be picking them, appearing with a ladder at dawn to claim each day’s haul.

It’s taken me a while to work out how the Cypriot seasons work. The almonds, figs and pomegranates are ripening now, the olives are heavy on the branches, but the citrus fruits are still young and green. Last year, when winter arrived, I eyed them sadly, presuming they’d missed their window and were starting to ripen too late. Then I watched as they fattened in the winter rains and turned yellow and orange at the coldest point in the year, hanging in the valley like thousands of lanterns, with snow on the mountains behind them.

Grass grows in the winter too and, for a few months, this parched place becomes shockingly green. Then, in March the grass dries out, the farmers cut it and hay bales glow in the fields. A sight that I associate with the end of summer coincides here with the start of spring.

Having grown up with a fixed idea of what should happen in each season, Cyprus has shown me that there is nothing universal about that pattern, and that growth and ripening, rest and renewal sometimes work to different schedules.

Last week I wrote about neighbourliness and community. I ended my letter asking:

What would happen if the boundaries between social institutions and their communities were much more permeable?

And what would happen if communities had ways to routinely come together to address their most urgent crises?

This week I’d like to write about an organisation that provides a striking response to both of those questions. It’s called L’Arche and it’s a network of communities for adults with learning disabilities who cannot live independently. Although that’s not how they would put it, and the fact that I default to those terms is part of the reason L’Arche needs to exist.

L’Arche describe its communities as places where people with and without learning disabilities live a shared life, ‘allowing each other to benefit from living together, working together and learning from one another.’ L’Arche creates homes for people who could not live independently, but its aim is not to provide fixes for systems that marginalise adults with learning disabilities. Rather it exists to ‘model a human society where every life is of equal value’ and to challenge people to ‘imagine the world differently.’

At its simplest, each L’Arche community is made up of a few houses. In each house, a group of adults with learning disabilities live with a smaller group of people without learning disabilities, who tend to stay for one or two years. Life consists of work and play, cooking and eating, cleaning and admin, friends and family, sorrow and celebration.

As a twenty-year-old looking for something to do with a university year abroad, a friend told me about L’Arche. I moved to their community in Paris at the end of an August heatwave, dragging my bags to a little white-brick house on a narrow street in the south of the city and installing myself in a room not much larger than a lift. Six adults with learning disabilities lived there – three men, three women, aged between 25 and 55 – and two other volunteers.

Our house was part of a community of several houses, all within a five-minute walk of one another. The night I arrived there was a community party at our place and I found myself in a crowded kitchen dancing to classic French disco. As well as several other volunteers with patchy French, I met some of the community’s permanent residents: Alain who loved wearing ties and telling people how elegant it made him feel, bald Emmanuel who asked if I would stick the hair back on his head, Claire who told and retold the story of her brother’s death in a motorcycle accident two decades earlier, Francois who stood very straight, smiled almost constantly and liked to look at people then quickly look away when they looked back. Some people spoke more, and more quickly, than anyone I’d ever met, others spoke little or not at all. We ate and danced and drank shandy, the kitchen doors thrown open onto the courtyard and the windows thrown open to the street in the hope of a breeze.

It was late when we finished cleaning up. I walked through the dark house to my little bedroom, encountering a surreal soundscape on the upstairs landing. One of my new housemates belched loudly and frequently in his sleep. Another slept with white noise, the sound of breaking waves, though for some reason the track included other sea sounds too: the screech of gulls and even an intermittent foghorn. She played it at maximum volume and the noise echoed along the landing. I was about to open my door when the door next to it sprung open. Another of my housemates popped out, wearing a lab coat and brandishing a wooden craft knife. “Bonne nuit, Matt!” he shouted before popping back into his room. Lying on my bed I left the blind open and watched the spotlight of the Eiffel Tower swing across the sky like the beam of a lighthouse, while I listened to the roar of the ocean.

There’s a lot to say about my time at L’Arche, but today I’d just like to write about Patrick, the oldest and quietest of my six housemates and the one who taught me most about growth and change and relationships.

Patrick was a five-foot, fifty-five-year-old French man with stubble, thick glasses and small, shaky hands. He was one of two people I had a particular responsibility to support. In Patrick’s case that meant supporting him to shower and shave, accompanying him to and from the community workshop where he worked, going along to medical appointments, and dosing out his daily allowance of two cigarettes.

Patrick was not an easy person to get to know. When he first met you, he would cock his head to the left, purse his lips and squint, as though sizing you up. He could communicate well but had little language and would most often tug your sleeve and point if he needed help. He enjoyed being with people and would perform comic, exaggerated mimes that made everybody laugh, but he also liked his privacy and spent a lot of time quietly in his room, looking at his weekly football magazine, smoking his cigarettes, and – in the middle of the night – completely rearranging his furniture, posters and possessions, so that when you entered his room in the morning you would do a double take and struggle to orient yourself.

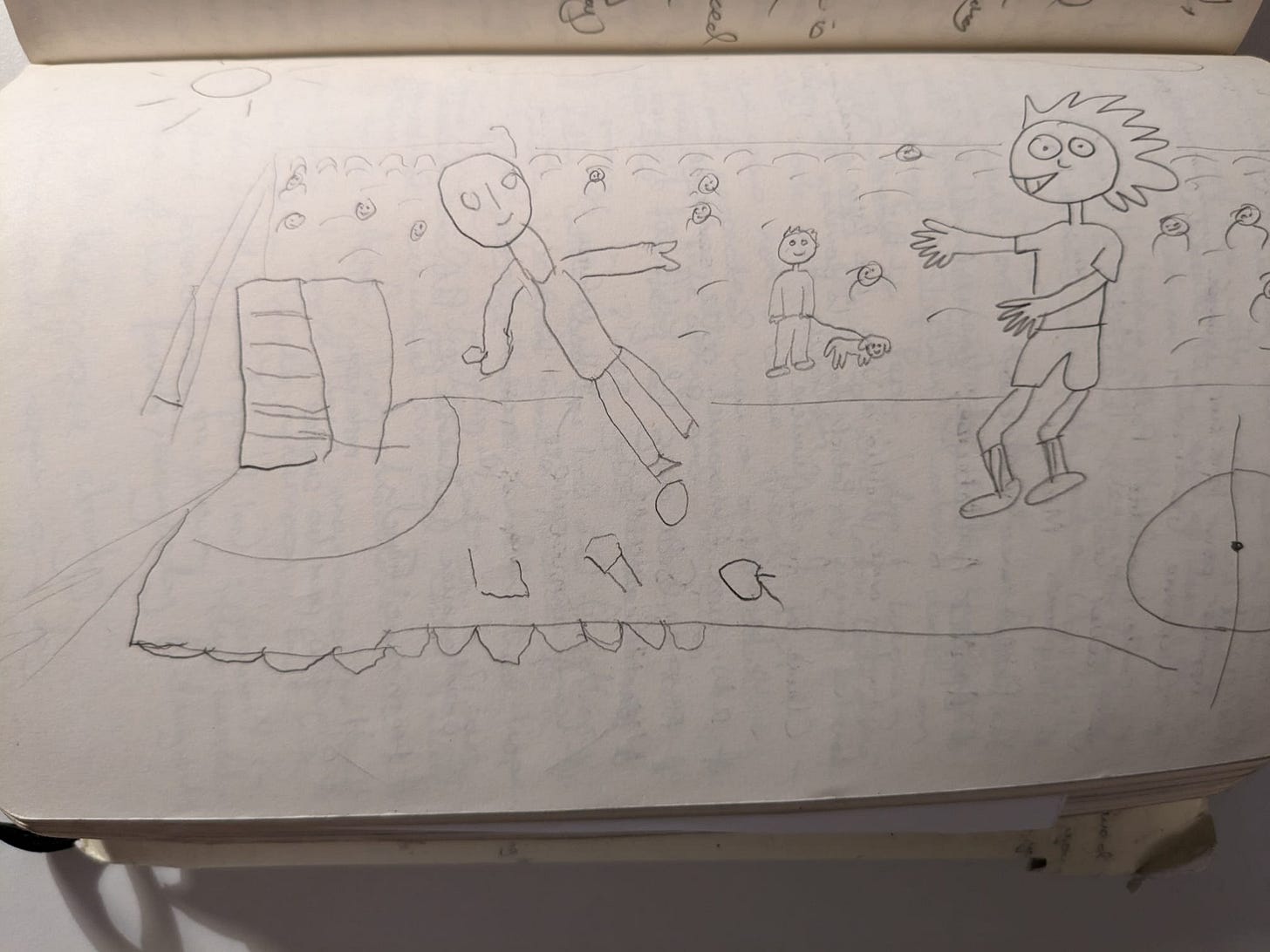

It took Patrick time to trust people – which was fine, because at L’Arche time was the main thing we had. Every morning we all had breakfast at our long kitchen table, every evening we had dinner together. Every Tuesday night we had a special meal where everyone would share how they were and how their week had been over an aperitif in the lounge, holding a candle when it was their turn to talk. Of an afternoon, Patrick and I would often pop to a café, order espressos and draw pictures together, taking turns to add elements to the scene. We would spend time with Francois too, the smiling man from the party. He worked with Patrick in the workshop and had even less language. Francois had never learned to talk and communicated mainly through eye contact, gestures and the beaming smile that he rarely turned off. We would walk to and from the workshop together and sometimes pop over for dinner at Francois’s house.

Patrick loved football, loved cigarettes and, inexplicably, absolutely loved the masked vigilante Zorro. At our Tuesday night aperitif, he would sometimes use his time with the candle to perform an extended mime in which he would thrust and parry with an imaginary sword before shouting ‘Bravoooo Zorro!” and then sit down. When the Antonio Banderas Zorro film came to the cinema, Patrick and I went to see it. He yelled ‘Zorro!’ every time Zorro appeared on the screen, which happens a lot, and which soon led to exasperated shushing by the people around us.

Patrick was a very mellow person to be around. We would walk through our neighbourhood, his hand crooked over my arm, and the better we got to know one another, the more easy and companionable that felt. But he was far from mellow when he first joined the community. He was one of many people there with harrowing backstories.

Unlike the community members with Down Syndrome or Autistic Spectrum Conditions, for example, Patrick wasn’t born with a learning disability. Instead he caught meningitis as a baby, which severely affected his development. When his family realised the extent of the impairment they abandoned him and he lived, until he was thirty-five, in psychiatric institutions, with limited contact with other people. He couldn’t speak and was often violent. Before he was invited to join the L’Arche community in Paris, he had spent his whole life essentially incarcerated.

People who knew Patrick when he first arrived in 1980 describe how frightened and wounded he was: violent, unable to trust anyone, unfamiliar with even the concept of forming meaningful relationships. He often lashed out and often ran away.

He was always found and always welcomed back and, over years of spending time with people who knew him and cared about him, he learned to trust, to feel at home, to say some words, to do his own laundry, to draw pictures and to write his surname. He settled into himself and people came to know and like him for who he was.

Although Patrick had mellowed we still saw flashes of the old fear. One evening he felt threatened by another housemate and I had to jump up and catch him mid-lunge. There were also moments of wily cunning, like the time he spied on us to find out where we stored his cigarettes, then took the stash and smoked two packs in a night.

Each morning I walked with Patrick to the community workshop where he made arts and crafts items to sell at events. One day I stayed to join in with a gardening session, reseeding the lawn. The head of the workshop put on a Viennese waltz and we promenaded around the garden in time to the music, twirling, laughing and tossing handfuls of seeds in the air.

Spending time with Patrick challenged my ideas about deep relationships needing to emerge from shared interests, or shared characteristics, or good conversations. I don’t like football or cigarettes. I like Zorro a little more, but it’s still not quite my thing. Getting to know Patrick involved being in each other’s company for hundreds of undramatic hours; it happened in thousands of repetitive acts, in the moments between anything in particular happening.

I recently found a short report I wrote at the end of the year. ‘Life at L'Arche is stripped back to the bare essentials,’ I wrote. ‘Human relationships are privileged above all else. There is little adornment, you are simply living in a house with a group of people, getting to know them, and facilitating day to day life.’

L’Arche communities are not perfect. They are real places where real things go wrong and where problematic power dynamics can develop. There is a constant tension between structure and flexibility, between mitigating risks and giving people space to live their lives. The organisation itself is currently reeling from revelations of abuse by its revered founder.

Nonetheless it’s a place that helps me imagine society differently. Instead of defining adults with learning disabilities by their needs, L’Arche highlights that everyone, with or without disabilities, has different needs and different gifts, and that if we create communities with the space for mutual exchange, those gifts can be given and those needs can be met. My time in the community made me wonder where else a symbiotic, relationship-centred approach could transform our response to our biggest social and ecological questions. How might other systems and structures look if they were designed around mutually transformative relationships?

After I left L’Arche a friend moved there. Later my sister went to live there, so for a few years I visited quite frequently. I would always go for coffee with Patrick and, on one trip back, after we’d been for an espresso, we went for dinner in the house where Francois lived. Francois waved and smiled as we entered. I smiled and waved back as I took off my shoes.

As I stood up, Francois walked over and put his hand on my arm. ‘Matt!’ he said, then burst out laughing. Everyone else laughed too. I looked around in confusion as they explained that now, in his fifties, after a life without words, Francois had begun learning to talk.

Growth and ripening, rest and renewal sometimes work to different schedules.

Warm wishes,

Matt